Student Hunger is a Policy Choice

Is City College’s administration paying attention to the growing number of food-insecure students?

By Patricia Baldwin

Since its unveiling last August, the long-awaited Student Success Center gleams at all who pass City College on Ocean Avenue. External signs on every side trumpet “Student Success.” During the first week of the Fall semester, it was the busiest place on campus, with students flowing in and out.

But under the bustle of campus lay a hard truth — that a majority of the student body suffers from limited or uncertain access to food. According to a 2025 report from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, 70% of California community college students reported experiencing food insecurity.

This is not a new problem, only a more acute phase of an ongoing crisis. A 2017 survey of students enrolled in English courses at City College found that at least 41% were food-insecure. In response to this demonstrated need, the City College Food Pantry Work Group — composed of students, staff, faculty, and community members — created programs to get food to students. (Disclosure: This reporter is the former chair of the City College Food Pantry Work Group) Despite increased need, the college now seems to be abandoning these programs.

When I visited the Student Success building for the first time, I was looking for where the administration planned to host the weekly farmers’ market. In 2018, the Food Pantry Work Group facilitated a partnership between City College and the San Francisco/Marin Food Bank to provide weekly, farmer’s-market-style fresh food distribution to CalFresh-eligible students.

Over time, the market disappeared, another lifeline denied to students in need. Last spring, word around campus was that it would be restarted once the Student Success Center opened. Vice Chancellor Lisa Cooper-Wilkins recently reported to the Associated Students Executive Council that she was talking with the food bank about restarting the market. But the timeline remains unclear.

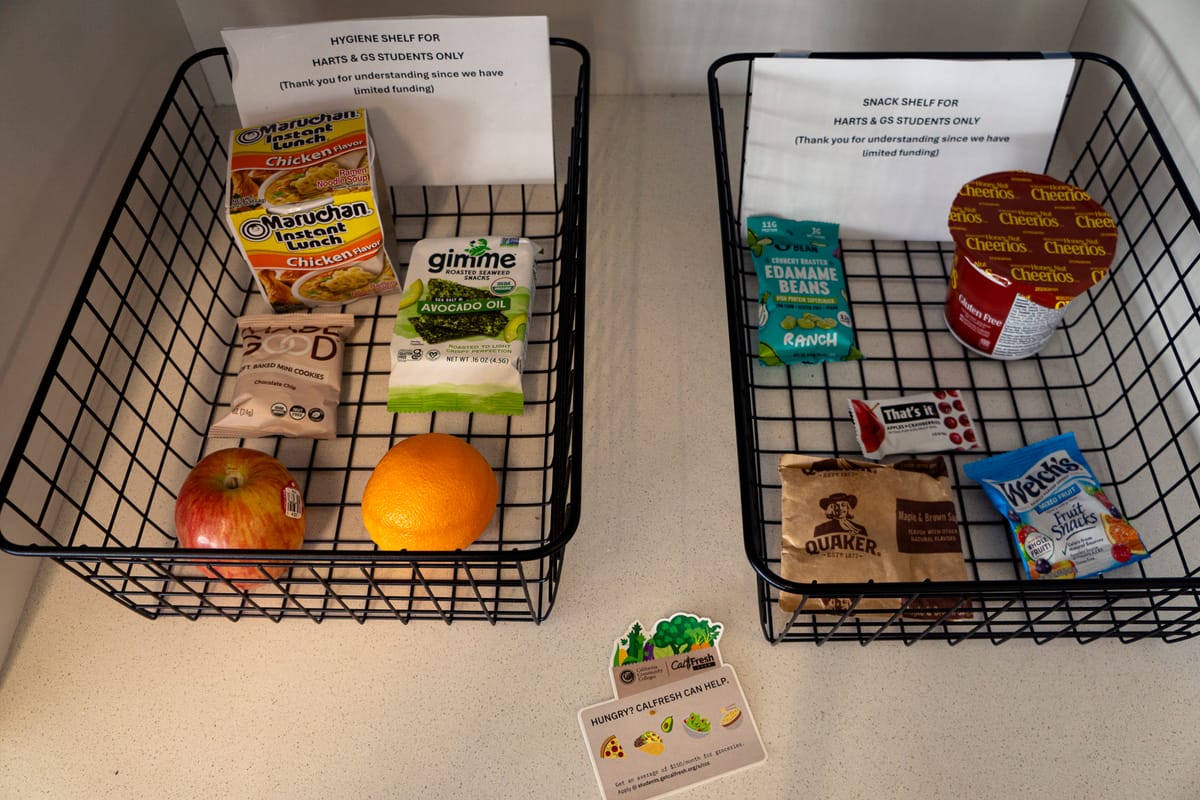

As I enjoyed the second-floor lounge in the Student Success building, I saw several students visiting resource centers to ask for snacks from the Snack Shelves. The Snack Shelves program — a 2018 partnership between then-Dean of Students Andrew King and the Food Pantry Work Group — was piloted as one prong of a comprehensive re-envisioning of efforts to feed students.

When it started, the Snack Shelves provided free, nutritious snacks at five locations across campus. Thankfully, the Office of Student Equity has since expanded the Snack Shelves program, providing free snacks at all City College campuses and at multiple locations on Ocean Campus.

However, with many of the resource centers having moved into the Student Success building, the Snack Shelves are being consolidated into one building, creating snack deserts across campus.

To make matters worse, the Office of Student Equity has considered discontinuing the Snack Shelves program. This Fall, SparkPoint CCSF Basic Needs Center stopped participating in the Snack Shelves program, and the Office of Student Equity stopped funding Snack Shelves in the Women’s Resource Center. City Dream has started restricting access to its Snack Shelf to its students only.

If the Office of Student Equity were to discontinue funding for the Snack Shelves, the resource centers would need to pull from their own budgets to make up the difference. According to Tyler Powers, Vice President of Finance for the Associated Students Council of Ocean Campus, the Queer Resource Center had already spent $5,000 on snacks and drinks for students as of November, when the Office of Student Equity closed nearby Snack Shelf locations.

For students who come to campus hungry, their options are dwindling. Snack Shelves should be expanded across campus, not contracted. Or does the administration want 70% of the student body descending on the Queer Resource Center’s Snack Shelf? If the Snack Shelves program loses its funding, those options will be even slimmer.

The impact on students at other campuses may be even more dire than at Ocean Campus. Research suggests that rates of food insecurity are higher among English Language Learners, immigrant populations and students in adult education programs, which make up a higher percentage of programs at City College’s other campuses.

The Food Shelves and the weekly fresh food market represent only what the Food Pantry Workgroup was able to accomplish. What about all the other wonderful ideas members of the campus community have suggested to support food-insecure students?

In tackling food insecurity at City College — a real, tangible problem — the administration needs to expand beyond the baseline of these two programs. How about a fully stocked food pantry in the Student Success Center, open every day, with nutritious food for students to take home?

Partnerships with community organizations could be another option. San Francisco-based Food Runners picks up excess food from businesses and delivers it to neighborhood food programs. The school also lacks a community garden, despite our amazing horticulture program.

City College does not have a representative on the Food Security Task Force, an advisory body to the board of supervisors that develops a citywide plan to address food security.

With new leadership at City College and a new building that trumpets “Student Success,” food insecurity needs to be treated as the crisis it is. How does Chancellor Messina plan to address significant levels of food insecurity among her institution’s student body? Why have we not heard about how she and her leadership team will confront this crisis?

Supporting student success is much more complex than putting that phrase on a building — it requires time, money and planning. So far, I am not convinced that the administration has a credible plan for addressing the level of food insecurity faced by City College students.